The People Who Built DESCO

Founders of Diving Equipment Company

DESCO was formed in late 1937 and organized as a Wisconsin corporation under the name of Diving Equipment and Supply Co in May of 1938. Its organization was the result of several events, which occurred during the preceding years. These events brought together a unique group of people. The Second World War transformed the company from a research and development firm to a major manufacturer. As time progressed diving technology moved forward. Innovative people kept DESCO a viable entity. To know the story of DESCOand our passion for diving equipment you need to know their stories as well.

Max Eugene Nohl

Maximilian Eugene Nohl was born in Milwaukee Wisconsin in 1910. His family was comprised of prominent local attorneys, with his Uncle Max being a judge. As a young boy he has a near drowning. Later his best friend drowns and Max finds his body three days later. He developed a fear of deep water at that time. Some time later he is under a sunken row boat breathing the trapped air and is fascinated with the underwater world. He reads about sunken treasure and is torn with conflicting emotions, not knowing if he can overcome his fear. An opportunity comes along to dive an open helmet made from a five gallon paint can. He seized the chance to face his fear and afterwards determines diving is going to be his profession.

Maximilian Eugene Nohl was born in Milwaukee Wisconsin in 1910. His family was comprised of prominent local attorneys, with his Uncle Max being a judge. As a young boy he has a near drowning. Later his best friend drowns and Max finds his body three days later. He developed a fear of deep water at that time. Some time later he is under a sunken row boat breathing the trapped air and is fascinated with the underwater world. He reads about sunken treasure and is torn with conflicting emotions, not knowing if he can overcome his fear. An opportunity comes along to dive an open helmet made from a five gallon paint can. He seized the chance to face his fear and afterwards determines diving is going to be his profession.

After high school Max attends MIT and studies mechanical engineering. He knows advances in diving technology will be driven by design and research.

In 1933 Max builds a diving sphere he called “Hell Below” after seeing Beebe’s Bathysphere on display in Chicago. He made up plans and had Falk Corporation fabricate it. His bell differs from Beebe’s in that it has motors for maneuvering underwater.

1934 finds him working as an assistant engineer aboard the ship Seth Parker for the Phillips Lord expedition. The voyage is plagued with problems and he jumps ship in Haiti on June 1st. While there local fishermen tell him stories of sunken Spanish galleons littering the Caribbean. He returns to MIT to finish school.

That summer he teams with Jack Browne and Vern Netzow to explore a sunken steamship off of the Milwaukee suburb of Fox Point. The expedition makes the July 15, 1934 edition of the Milwaukee Journal. Later in the month Max made the paper again when sailing with Miss Helen Koch, the catboat they were in capsized in a sudden squall. Unable to right the boat the two began to swim the three miles to shore. Miss Koch was also an excellent swimmer and made it to the swimming raft off shore of the Nohl home. Max who was not far behind Helen was picked up by a Coast Guard launch called to the scene by onlookers. They were taken back to the sailboat which was righted and the couple sailed it in, with the Coast Guard right behind.

In 1935 Max begins his salvage operations on a sunken steamship, the "John Dwight". The Dwight was a prohibition rum runner that came to a mysterious and violent end off Martha’s Vineyard. The local newspapers found it to be good copy and kept up on the progress. This brought Max to the attention of a Hollywood producer John D. Craig, who was interested in the possible salvage of the torpedoed Cunard liner, the "Lusitania," which lay in 312 feet of water off the Irish Coast. Max called Craig (who was in Boston at the time) to see if he would like to come down to the site, check out his diving gear, and shoot some film of the salvage. Craig agrees and ultimately ends up pitching in on the Dwight salvage by helping out with diving duties. Max had hoped to salvage the cargo and cash assumed to be onboard. The safe proved to be empty and seawater had entered the scotch which was ruined. Max had another close call when the mooring line parted and the dive boat went adrift, dragging Max off the wreck. His dress snagged and was torn, allowing the suit to fill to his ears. He just managed to keep his face high enough to breathe while they hauled him up.

The Dwight salvage cemented a friendship between Nohl and Craig and led them to the next adventure, The Lusitania. At that time, no equipment or reliable techniques were available for diving operations at such a depth, and it was obvious that such a project would require both physiological experimentation and an advance in diving equipment design. 1935 also brings an end to his academic activities. He graduates from MIT with a B.S. in Engineering. His thesis “Diving” covers his knowledge of and ideas for diving and equipment innovations. He outlines his idea for a new type of diving gear. While waiting for the Lusitania contracts to come through, and to earn money for new diving gear, Max takes on salvage jobs and has a few near misses, losing consciousness on one job, and getting squeezed on another.

1936 finds Max back in Milwaukee with Jack Browne designing and building the equipment to work on Lusitania. Max and Jack mounted an expedition in 1936 to salvage the lake steamer Westmoreland in Platte Bay on Lake Michigan.

January 19, 1937 The Wisconsin News publishes an article on Craig’s and Nohl’s plans for the “Lusi”. On March 2, 1937 a photo appears in The Milwaukee Journal of Max testing the new rig in the swimming pool of the Milwaukee Athletic Club.

Through 1937 Nohl and Dr. End experimented with Helium in the recompression chamber at Milwaukee County Emergency Hospital, and worked on refining and testing the diving rig. A preliminary test dive was made from USCGC Antietam in the fall to a depth of 58 feet. On December 1st the record attempt was made. Max changed the plan of a descent to 350 feet to a bottom dive at 420 feet. The dive was carried live coast to coast on NBC radio.

The success of the test dives lead Nohl and Browne to form Diving Equipment and Supply Company. DESCO would be responsible for manufacturing and procuring the needed equipment for the Lusitania expedition. Jack Browne was to be president of the firm but he would not turn 21 until spring. The incorporation of the company was delayed till May 1938 when Jack achieved majority. Financing and housing of the new firm were provided by Norman Kuehn and the Kuehn Rubber Company. Max held no financial stake in the company (Jack Browne did) and was termed an employee.

On December 22, 1938, Edgar End and Max Nohl made the first intentional saturation dive by spending 27 hours breathing air at 101 feet in the County Emergency Hospital recompression facility in Milwaukee Their decompression lasted five hours leaving Nohl with a mild case of decompression sickness that resolved with recompression.

With a new war looming over Europe the British Admiralty kept adding restrictions to diving on the Lusitania so that the whole project was abandoned. Max was not sure the new company could survive in a competitive commercial market decided to lecture and exhibit his underwater films. His lack of financial or administrative ties to the company allowed him an easy exit. A plan surfaces in late 1938 or early 39 to use the new diving rig in the Caribbean searching for treasure ships. Max’s underwater filming experience leads him to Florida. He was hired by Newton Perry to work on the Tarzan films starring Johnny Weissmuller. Accompanying Max to Florida were James Lockwood, and Ivan Vestrem. While there he designs and builds an multi person diving bell to give tourists an underwater view of Silver Springs, as a diver would see it.

After Pearl Harbor Max enters the Florida sponge diving industry. Sponges are a necessary war material. His diving team sets up in Louisiana and he meets his future wife Eleanor. She makes one dive and blows up to the surface. He also made attempts to get salvage contracts for sunken merchant ships in the Gulf of Mexico. Red tape, shortages, and restrictions hamper the effort.

The war ends and the sponge market collapses. Max returns to commercial and salvage diving. The years after the war saw Max involved in underwater salvage work, commercial diving, sub-marine contracting, and underwater motion picture work. Also during this time Max became a public celebrity. He appeared in product ads for Blatz Beer and Imperial Whiskey. He also appeared on the TV show "What's My Line". After several close calls he decides to return to DESCO and try a more “normal” lifestyle. He stays through the Korean War but as post war business declines Max decides move on to start his own company.

On page 12 of the June 1954 issue of Skin Diver Magazine an article appears, “NEW UNDERWATER COMPANY ANNOUNCED”. Max opened American Diving Equipment Company on 54th & North Ave. in Milwaukee. ADE was to provide a wide array of equipment to sport divers. It would also be a dealer for DESCO products and Max was still acting as a technical advisor to DESCO. The new venture was an almost immediate success with orders coming faster than they can be filled. ADE didn’t last long as another event captures Max’s attention. On October 14, 1954 the cargo ship MS Prins Willem V collided with the barge Sinclair XII and sank outside the Port of Milwaukee. The wreck site was only six miles from the Nohl’s front door. ADE was dissolved in late 1954 when Max won rights to salvage the sunken freighter Prins Willem V off Milwaukee Harbor.

The US Army Corps of Engineers determined the wreck was above the 41 foot depth requirement and sought bids for clearing the obstruction. Max entered a bid and won the contract. USACE would pay $50,000 plus salvage rights to the ship and cargo. Winter prevented the start of work. In the spring of 1955 work began and a legal battle with the Corps of Engineers was on the horizon.

Upon inspection Max found a gangplank floating up from the wreck. He cut it away and the wreck now was at 41feet 6 inches, below the legal requirement. A year and a half legal fight ensues until USACE and Max settle out of court. USACE felt $50,000 was unjustified for 5 minutes work. After some negotiation Nohl settled for $47,000 plus rights and the Corps agreed since both parties had entered the project in good faith. Nohl had his salvage rights to the Willem and he made plans to raise the ship.

The first attempt to raise the Willem in 1956 failed and more legal problems arose. He had divers working on a share basis but the plan to float the vessel could not be made workable.

In 1958 a new venture was mounted. Nohl formed Seaboard Excavators Inc. to make this attempt. He forms a salvage company with Armando Conti who is trying to salvage the Italian Liner Andrea Doria. Max receives a stake in the Doria salvage in exchange for part of his rights to the Willem. After a summer and fall of trying the Willem was still on the bottom and $200,000 was spent and the company is bankrupt by years end. Again the legal specter raised it head. The diving supervisor and the remaining salvage crew absconded with the salvage barge. The U.S. Marshal forced them into Sheboygan and the barge was returned to Nohl.

In October of 1959 things are looking up as Max secures a new backer, Robert Meissner, President of Meissner Engineering Inc. of Chicago. They formed Willem Salvage Corporation. After a trying year Max and Eleanor decided to take a vacation in Mexico anticipating a new start on “Willie” in the spring of 1960. It was not to be.

On Saturday February 6, 1960 while returning from their vacation Max and Eleanor Nohl were tragically killed in an automobile collision near Hope, Arkansas. Killed in the other car was Jesse Belvin and wife JoAnn. Belvin was a rising R&B singer and co-writer of the 50's hit Earth Angel.

John W. (Jack) Browne

Jack Browne was also a survivor of tin can diving as a boy. His father was an executive with the Goodrich Transportation Company in Milwaukee. Jack became interested in diving while a freshman in high school. He would take on jobs for pay or just dive for fun. He also had a knack for invention and his first diving helmet was literally a tin can. In 1934 he was working with Max Nohl diving on local wrecks. A captioned photo appears in The Milwaukee Journal April 4, 1935 of Jack and his friends Paul Gallun, Fred Lange, and Bob Wescott testing a home made diving helmet in a Shorewood swimming pool.

Jack Browne was also a survivor of tin can diving as a boy. His father was an executive with the Goodrich Transportation Company in Milwaukee. Jack became interested in diving while a freshman in high school. He would take on jobs for pay or just dive for fun. He also had a knack for invention and his first diving helmet was literally a tin can. In 1934 he was working with Max Nohl diving on local wrecks. A captioned photo appears in The Milwaukee Journal April 4, 1935 of Jack and his friends Paul Gallun, Fred Lange, and Bob Wescott testing a home made diving helmet in a Shorewood swimming pool.

When Max Nohl and John Craig began work on the equipment for the Lusitania salvage Jack was ready to pitch in. The custom diving dress they needed was stitched together from canvas and taken to the N.L Kuehn Rubber Company to be made watertight. Norman Kuehn was to become a mentor to Jack and an angel to the new company. The Nohl, Browne, Craig collaboration in 1937 resulted in the forming of Diving Equipment and Supply Company. Jack was to be president of the new firm but there was a problem. As a principal in the corporation he needed to be 21 years old. DESCO would not be formally incorporated until May of 1938 when Jack became “legal”. Mr. Kuehn signed on as Vice President, and a local attorney Earl Wanacek as secretary/treasurer.

DESCO was located in the Kuehn Rubber Co. facility on north 4th street. Kuehn himself provided financial support and business advice. After the Lusitania project collapsed and Nohl and Craig had moved on to other things Jack determined to keep DESCO alive. Through 1938 to December of 1941 the small firm plodded along. Jack experimented with new designs for breathing tanks and lighter suits.

With the outbreak of World War Two Mr. Kuehn urged Jack to go to Washington. “Tell the Navy what you know about diving suits. Show the boys what you have done and can do.” Jack did. In January of 1942 he headed east and returned with a $5000 order for three self-contained suits. That first order led to others until DESCO was producing more diving equipment than anyone else in the world.

Jack and DESCO were major contributors to the Navy war effort. DESCO/Navy collaborative efforts led to the development of the Browne Mask, Lightweight Diving Suit, and Buie Diving Helmet. Navy Doctor Albert Behnke worked with Browne and Dr. End on refinements in deep diving on Helium. Emerson Buie came to DESCO with his idea for a low volume diving helmet to deal with mine clearance in harbors. The US Office of Strategic Services asked Jack and DESCO to build them compact Oxygen rebreathers for covert operations. Along with special development projects was the day to day operation of a company supplying 80% of the country’s diving equipment needs.

By 1945 DESCO had its own pressurized wet tank for research and development. On April 27, 1945, Jack used this tank to "dive" to still a new record depth of 550 feet of seawater. As in the case of Nohl's earlier dive, he breathed a heliox mixture under the supervision of Dr. End. Both dives were milestones in the development of modern techniques of mixed-gas diving. Max Nohl was asked how he felt about Jack breaking his record. Max replied "records are made to be broken".

In 1946, Norman Kuehn and Jack Browne sold the company to the general manager E.M Johnson and a group of investors.

Jack moved on to help run the family automobile dealership Browne Motors Chrysler Plymouth on 20th Street & North Ave. in Milwaukee. In June 1949 he became president of the dealership after his father George passed away.

Jack makes the local papers occasionally, most notably for a bridge on the Fox River in Green Bay having to open so he could land his seaplane. He also made the paper with a story on the spider monkey he keeps on his yacht.

Not much more was heard from him until 1958 when he is flying guns to Fidel Castro's Cuban rebels. He is forced down by the Batista Cuban Air Force and imprisoned. Browne managed to escape from prison and steal back his plane. On the flight to Florida he runs out of fuel over the Florida Keys. He was rescued by the Coast Guard.

Jack retired to the Virgin Islands and passed away in 1998 from a heart attack.

Dr. Edgar End

Dr. Edgar End also was a survivor of tin can diving in his youth. He made a helmet from a can, used a tire pump and garden hose for air, and sash weights tied to his belt. He did this to attempt to recover a friend’s lost eyeglasses. Edgar was a graduate of the Marquette University Medical School and was a practicing physician. He served as Assistant Clinical Professor of Environmental Medicine at MU. In this capacity he was studying the effects of Caisson Disease on Milwaukee tunnel workers. In April 1937 Max Nohl contacted him about his development of Helium/ Oxygen decompression tables. Dr. End suggested using the recompression chamber in the basement of the Milwaukee County Hospital to test their theories.

Dr. Edgar End also was a survivor of tin can diving in his youth. He made a helmet from a can, used a tire pump and garden hose for air, and sash weights tied to his belt. He did this to attempt to recover a friend’s lost eyeglasses. Edgar was a graduate of the Marquette University Medical School and was a practicing physician. He served as Assistant Clinical Professor of Environmental Medicine at MU. In this capacity he was studying the effects of Caisson Disease on Milwaukee tunnel workers. In April 1937 Max Nohl contacted him about his development of Helium/ Oxygen decompression tables. Dr. End suggested using the recompression chamber in the basement of the Milwaukee County Hospital to test their theories.

Dr. End worked closely with Nohl and Browne during the construction of the Lusitania diving outfit. A great deal of physiological study was needed to make sure a human could work in deep water safely. This research allowed Dr. End to revise his diving tables.

On December 1, 1937 Max Nohl succeeded in diving to a depth of 420 feet, thereby breaking a depth record which had been held by a U.S. Navy diver Frank Crilley, since 1915. Nohl accomplished this feat using DESCO's new diving equipment and breathing a heliox mixture prescribed by Dr. End. Nohl managed to throw End a curve ball during the dive. He decided that he wanted to continue past the 350 foot target depth all the way to the bottom. The decompression tables had been worked out to 375 feet as a precaution. This forced Dr. End to pull out his slide rule and re-compute his decompression stops to the new depth.

The End-Nohl collaboration extended beyond the Lusitania project. In 1937 they designed and built a SCUBA rig, five years before the Aqua-Lung. After thorough testing in the hospital chamber and lake Michigan the SCUBA rig and Dr. End accompanied John Craig to the West Indies to search for Spanish treasure ships in 1938-39. He served as the expedition doctor.

Also in 1938 End and Nohl did their first tests in saturation diving. They stayed in the hyperbaric chamber for 27 hours at a simulated depth of 102 feet.

During World War Two Dr. End worked with DESCO and the U.S. Navy on new equipment and technologies. He was also in demand from the U.S. Army Air Force to help them with the problem of high altitude bends.

After the war he continued his research into the therapeutic benefits of Oxygen under pressure in the treatment of disorders where body tissues are deprived of Oxygen. His studies are some of the underpinnings of modern hyperbaric medicine. Treatment of carbon monoxide poisoning, stroke, and other diseases which inhibit oxygen absorption is commonplace now in no small measure due to Dr. end’s efforts.

Dr. End passed away in 1981 at the age of 71.

Dr. Eric Kindwall published his autobiography called Unexpected Odyssey, and in it he relates meeting Edgar End in about 1950 when he was a teenager. Through End he also met Max Nohl.

It was about this time that I met Dr. Edgar End, introduced to me by my father. Dr. End was a general practitioner with an office over Paulus's drug store in downtown Wauwatosa. Edgar End had also been interested in diving. As a boy he had built his own diving equipment and oddly had also used sash weights in the pockets of an overcoat to hold him on the bottom. In 1937, while he was a 26-year-old intern at the Milwaukee County General Hospital, he thought that helium would make an ideal diving gas as Behnke had shown in 1934 that nitrogen in the air was responsible for nitrogen narcosis at deep depths. Helium was much less soluble in fat so according to the Meyer-Overton hypothesis should have very little narcotic effect. The Royal Navy had tried helium in the 1920s, as had the U.S. Navy, but both had abandoned it as impractical because it caused the bends, despite extra-long decompression times. End realized because of its really fast diffusivity, very deep decompression stops would have to be used. With this new concept, he devised new decompression tables and tested them on himself in the recompression chamber at the old Milwaukee County Emergency Hospital. He didn't get bent, so realized he was on to something. He managed to interest a Milwaukee diver, Max Gene Nohl, an MIT graduate engineer, in his ideas.

Nohl had designed a hardhat self-contained diving rig that was well suited to trying out the new gas mixture. In December of 1937, Nohl descended to 420 feet off Port Washington in Lake Michigan to establish a new world record for depth. Nohl and another Milwaukee diver, an adventurer named Jack Browne, later established the Diving Equipment and Supply Company in Milwaukee (DESCO) that supplied over half of all the diving equipment for the U.S. Navy during World War II. End was the first to routinely use low-pressure oxygen treatment for decompression sickness ("the bends") in 1947. The U.S. Navy adopted it 20 years later and reduced their treatment failure rate from 47.1 % to 3.6%.

Dr. End introduced me to Max Nohl. I went to his apartment for my first meeting with him, expecting to find a real gorilla of a man who was able to withstand the crushing depths of 420 feet of water. Instead, I found a man of slight build wearing glasses who looked like a bank clerk! He had "just come out of the water," having tested that morning some new gear in the "wet pot,' a diving test tank they maintained at DESCO. I described my diving gear to him. In essence, he said, "Kid, get yourself some decent diving gear or you're going to get yourself killed!"

Excerpt from Unexpected Odyssey by Eric Kindwall Best Publishing Co. Eric Kindwall M.D. now retired, was Director of Hyperbaric Medicine at St. Luke's Medical Center in Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Bernice McKenzie

In October of 1942 Diving Equipment & Supply Company placed advertisements in Milwaukee newspapers seeking applicants for job openings in their plant. A patriotic young woman seeking work in a defense industry came in for an interview. She was told the opening was for a solderer. Although she had no experience they took a chance on her. Two women were already soldering for DESCO but were leaving the company for other jobs. They took three weeks and trained the young woman before they left. She was the lone solderer for about a month before another girl was hired. Within six months the soldering department had eighteen women and all were trained by her.

In October of 1942 Diving Equipment & Supply Company placed advertisements in Milwaukee newspapers seeking applicants for job openings in their plant. A patriotic young woman seeking work in a defense industry came in for an interview. She was told the opening was for a solderer. Although she had no experience they took a chance on her. Two women were already soldering for DESCO but were leaving the company for other jobs. They took three weeks and trained the young woman before they left. She was the lone solderer for about a month before another girl was hired. Within six months the soldering department had eighteen women and all were trained by her.

That is how Bernice McKenzie came to be at DESCO. A desire to contribute to America’s war effort and a solid work ethic made her an invaluable addition to the company. What the interviewer must have seen in Bernice moved her up through the ranks in the company in a career which spanned forty seven years.

As the war progressed and more work came DESCO’s way Bernice was moved to other departments and given more responsibilities. She spent time in the experimental room working with E.D. Buie on his helmets. As he came up with new or revised plans the helmets would get reworked. Bernice also worked on some of Jack Browne’s experimental projects. In 1950 she also had the opportunity to work with Max Nohl in the experimental room. By this time she had worked in and supervised every department in the company.

That same year, after eight years of bouncing around all the departments, she asked one of the boss’ “why are they doing this to me?” His reply was “can’t you guess?” Surreptitiously she was being trained in supervising each department in preparation for the next step in her career. Not long after that conversation Bernice was promoted to vice-president.

For nearly forty years Bernice managed a company in a male dominated industry. In reviewing interviews she had done it is obvious she never felt discriminated against. In fact it appears there was mutual respect and affection. Bernice never tired of talking with divers around the world.

In December 1989 she retired after suffering a heart attack and stroke. Bernice passed away on March 28, 2000 at the age of 88.

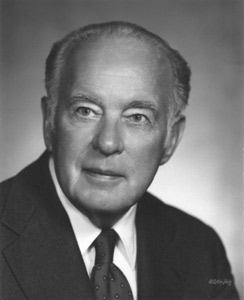

Thomas B. Fifield

Thomas Burns Fifield was born in Janesville, Wisconsin on October 9, 1915 to Dr. George Waterman and Elizabeth (nee Weidensall) Fifield. He received his BA at Princeton University in 1937. He continued his studies at the University of Paris, and Princeton University.

Thomas Burns Fifield was born in Janesville, Wisconsin on October 9, 1915 to Dr. George Waterman and Elizabeth (nee Weidensall) Fifield. He received his BA at Princeton University in 1937. He continued his studies at the University of Paris, and Princeton University.

In 1941, he entered the University of Wisconsin Law School but left to join the US Army in 1942, where he was a captain in the artillery. Mr. Fifield served 4 years in World War II mostly with the Third Armored Division Artillery in Europe. He entered France shortly following D-Day, and was at the Battle of the Bulge in December of 1944. After the war ended he stayed in the military serving as an advocate in the War Crimes Commission.

He was discharged in 1946 and returned to The University of Wisconsin Law School. On February 26, 1949 he married Marilyn Jean Kieckhefer of Milwaukee. In 1947 he received his LLB from the University of Wisconsin and practiced law in Milwaukee from 1947-50.

After graduating the top of his class at UW Madison he moved to Milwaukee and joined the firm of Miller, Mack and Fairchild, later Foley and Lardner.

As a member of the National Guard, he was called up in 1950 to serve in Korea, after training at Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

He returned to his law practice in 1952. From 1952 until 1966 he continued his law practice with increasing interest in sport and archaeological diving.

In 1963-69 he was chairman of NSIA AD HOC Committee to review evaluate design of conventional Navy diving gear. Final report of Committee submitted to Assistant Secretary of Navy for Research and Development on November 25, 1969.

In 1964, Thomas left Foley and Lardner and after a short law practice on his own, he joined Gibbs, Roper and Fifield as a partner.

In May 1966, Thomas and Marilyn Fifield purchased DESCO.

In 1968 DESCO moved to its present address at 240 North Milwaukee Street in Milwaukee. This location offered a home for the company and offices for his law practice and Mrs. Fifield who was serving on several corporate boards.

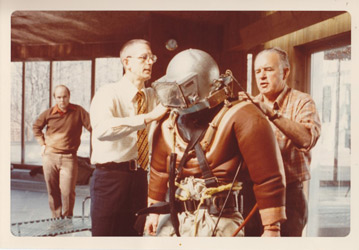

Mr. Fifield was responsible in the 1960's for the design and development of the DESCO Diving Hat, which remains a standard piece of modern equipment for diving with air in relatively shallow water where mixed gases are not needed.

Upon urging from Ronnie Temento (New Orleans SCUBA/Commercial diving shop owner) went to New Orleans to observe commercial divers using modified motor cycle helmets for shallow water diving. Mr. Fifield came back to Milwaukee and designed & tested the DESCO Air Hat which is the hat of choice for contaminated diving including nuclear work. Mr. Fifield worked closely with the staff on the design of the helmet. He assisted in fabricating parts for the prototypes. He built a indoor pool in his house where testing was conducted. Not only testing the Air Hat itself, but it's use in conjunction with other pieces of equipment like the Unisuit.

|

|

|

Mr. Fifield was a busy man. Besides DESCO he had a steady law practice, owned John L Chaney Instrument Co., served on several boards, edited a newsletter for the Friends of the Milwaukee Public Museum, was a member of the Milwaukee Zoological Society, was a private pilot and served as president of the Aerostar Owners Association.

He was an active owner staying in touch with customers and dealers. Being a pilot he could make personal visits and would often stop in when traveling. He would make an effort to be at shows with the dealers.

|

|

As time passed he depended more on Bernice McKenzie to run the ship as Marilyn and him enjoyed later life. More of their time was devoted to the Zoological Society and The Milwaukee Public Museum. They often went to Costa Rica where MPM owned land maintained as natural habitat. He also had a talent for gourmet cooking. His duck press would find it's way to DESCO for a polishing every few years. Mr. Fifield owned a 1970 Pontiac GTO convertible he bought new, and drove it daily until he was no longer able.

Mr. Fifield passed away on February 9, 2007 at age 91.

Wisconsin Innovations Exhibit and Thomas Fifield

In early 2011 DESCO was approached by staff from the Wisconsin Historical Society for information and artifacts for part of a new exhibit they were working on. The exhibit entitled Wisconsin Innovations was to showcase the Wisconsin people and inventions that have contributed to society. Mr. Fifield was chosen to be part of the exhibit because of his development of the Air Hat. We made prototype #1 and a polished Air Hat available, plus some photos.

0 Item(s)

0 Item(s)